Tackling a book in Spanish

Sometimes, even if you’re only a beginner in Spanish, you should try and read something a little more advanced.

Even if you only manage to read and understand one sentence, you might pick up something—a new word or a grammatical structure. This could lead you to form new sentences using that word. Or, even if you don’t fully understand even a single sentence in the book you’re reading, it might still help you grasp something else you previously struggled with. Reading something in Spanish is never a waste of time.

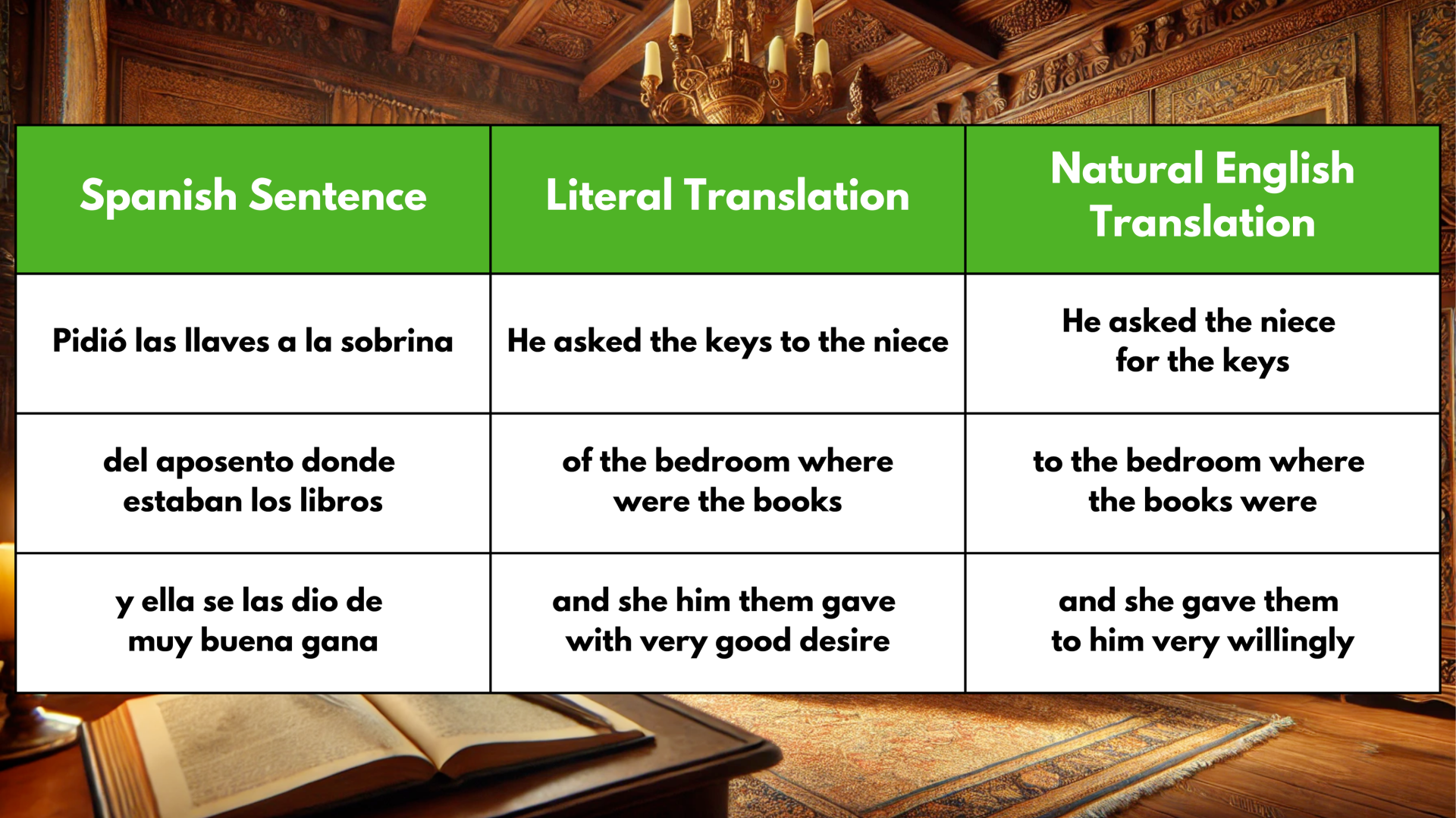

Pidió las llaves a la sobrina del aposento donde estaban los libros, y ella se las dio de muy buena gana.

This quote above is from a famous Spanish novel called Don Quixote by the writer Miguel de Cervantes.

The story follows Alonso Quixano, an aging nobleman who becomes obsessed with stories of knights and chivalry. Immersing himself in these stories, he decides to reinvent himself as Don Quixote de la Mancha, and sets off on a quest to revive knighthood. I chose this quote because it marks a pivotal moment in the novel.

Don Quixote owns hundreds of books about knights and heroic adventures, spending countless hours lost in their pages. His library—the aposento—symbolizes his obsession, and his family grows increasingly concerned about how much time he spends there.

Pidió las llaves a la sobrina del aposento donde estaban los libros, y ella se las dio de muy buena gana.

He asked the niece for the keys to the bedroom where the books were, and she gave them to him very willingly.

Firstly, this sentence seems all muddled up if you translate it word for word:

❌ “He asked the keys to the niece of the bedroom where were the books, and she him them gave very good desire”

It makes no sense. And this is an important thing to note about Spanish; if you translate it word for word, a lot of the time, it won’t make sense.

✅ “He asked the niece for the keys to the bedroom where the books were, and she gave them to him very willingly”

Now, let’s break it down, and look at how I got the English translation.

Pidió - He asked

This comes from the verb “pedir”, which means “to ask” or “to request”. It’s actually part of a phrase “pedir algo a alguien”, which means “to ask for something from somebody” or “to request something from somebody”.

For example, you could say things like, “Voy a pedir agua a ese hombre” meaning “I’m going to ask that man for some water” or literally, “I’m going to request water from that man”

The word “pidió” is in the preterite tense, which is a past tense. And it’s in the “he/she” form, so “pidió” can mean “he asked” or “she asked”

a la sobrina - the niece

The word “sobrina” means “niece”. In this sentence, it is part of the “pedir” phrase. He’s asking the niece for something. The “a” is because when you use the verb “pedir”, you have to put the word “a” in front of the person you’re asking.

las llaves del aposento - the keys of the bedroom

This phrase is split up in the sentence, and a lot of Spanish scholars said it seems like it’s a mistake. The way it’s split up makes it seem almost like an afterthought, “He requested the keys from the niece, for the bedroom”. “La llave” means “the key”, so “las llaves” is the plural meaning “the keys”.

The word “del” is the contraction of “de + el”. It means “of the”.

The word “aposento” means “bedroom” or “chamber”, and it tends to refer to the rooms in a very large house, or a palace. Normally, the word for bedroom is “habitación”.

donde estaban los libros - where the books were

In Spanish, the subjects of a verb can really be placed anywhere in the sentence. Very often they are placed after the verb, whereas in English they are placed in front of the verb.

In English, the phrase “donde estaban los libros” would be “where the books were”. In Spanish, however, the author wrote it as, “where were the books”, but it’s not a question.

You could, if you want, move the subject in Spanish, and say, “donde los libros estaban”, and that’s perfectly acceptable, too.

y ella se las dio - and she gave them to him

The word “y” just means “and”, and the word “ella” just means “she”. Oftentimes, the word “ella” is left out in Spanish; it’s only used to clarify who the subject of the verb is. Because in this sentence there is a “he” and a “she” mentioned, the word “ella” just makes it clear that it was “she” that gave them.

“Dio” is the preterite, or past tense, of the verb “dar”, which means “to give”. “Dio” can mean “he gave” or “she gave”, and so the “ella” clarifies that it means “she gave” in this sentence.

The verb “dar” in the preterite tense goes:

di - I gave

diste - you gave

dio - he gave / she gave

dimos - we gave

disteis - you gave

dieron - they gave

The “se las” part means “them to him”, and it’s referring to the keys. The “las” part means “them”, and it’s feminine plural because “las llaves”, which means “the keys” is feminine and plural.

The “se” part means “to him” and it should actually be “le”. The word “le” means to him usually. For example:

Voy a darle un libro - I’m going to give him a book / I’m going to give a book to him

Le he mandado todo - I have sent everything to him

The reason why it’s changed to “se” in this sentence is because when you put “le” next to either “lo”, “la”, “los” or “las”, it changes to “se”. This is simply because, in speaking, “se las” sounds better than “le las”.

Don’t worry if you don’t understand any of what I’m talking about. As I said, this is an advanced sentence for more advanced learners of Spanish. If you haven’t looked at these bits of grammar yet, you obviously won’t know what I’m talking about. Just take whatever you can out of this sentence, even if it’s simply that the word “las llaves” means “the keys”.

You can come back to this post whenever you want to get a bit more out of it.

So, let’s have one more look at the sentence in full in Spanish:

Pidió las llaves a la sobrina del aposento donde estaban los libros, y ella se las dio de muy buena gana.

He asked the niece for the keys to the bedroom where the the books were, and she gave them to him very willingly.

Sometimes, rewriting sentences so they make more sense in your mother tongue (or any language that you know well) is a good way to pick up new concepts. So, let me rewrite this sentence in Don Quixote, so you can make a bit more sense of it. All I’ll do is rearrange a few bits:

Pidió a la sobrina las llaves del aposento donde los libros estaban, y ella se las dio de muy buena gana

He asked the niece for the keys of the bedroom where the books were, and she gave them to him very willingly

Oh, that reminds me, I haven’t done the last little bit.

de muy buena gana - very willingly

The word “gana” means “desire” or “urge”. It’s a feminine noun, which is why “buena” is in the feminine form, too. So, “de muy buena gana” means “of very good desire”. Again, this is a time where you shouldn’t try to translate Spanish word for word, lest you end up more confused than when you started.

However, the phrase “de buena gana” should be learnt as a set phrase meaning “enthusiastically”. Therefore, “de muy buena gana” means “very enthusiastically” or “very willingly” — literally, “with much desire” or “with great eagerness”.

The opposite of “de buena gana” would be “de mala gana”, which means “unwillingly” or “reluctantly”.

There are also other phrases with the word “gana” that are useful to learn. “Con ganas” means “with enthusiasm”

Pedro ha hecho los deberes con ganas - Pedro did his homework with enthusiasm

Or, another phrase is “tengo ganas de”, which means “I fancy” or “I feel like”. You can put any verb on the end of this:

Tengo ganas de ir al cine - I fancy going to the cinema

You can also make it negative to mean “I can’t be bothered”

No tengo ganas de visitar Madrid - I can’t be bothered to visit Madrid

Summary

Takeaways

As I said, the sentence we looked at in this article is actually a very complex sentence, so it's certainly not for beginners. But that doesn't mean beginners can't take something from it. Here's a little takeaway box where I've condensed some key things from this article:

TAKEAWAY BOX

🔹 Pedir algo a alguien → To ask someone for something

🔹 Word order in Spanish can be different from English, but the meaning remains the same.

🔹 De buena gana means “willingly” and de mala gana means “reluctantly.”